welcome

|

||||||||||||

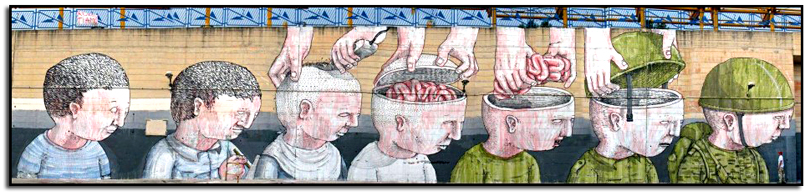

______WAR______ These 127 essays, although organized under seven headings, have one underlying theme: opposition

to the warfare state that robs us of our liberty, our money, and in some cases our life. Conservatives who decry

the welfare state while supporting the warfare state are terribly inconsistent. The two are inseparable.

Libertarians who are opposed to war on principle, but support the state’s bogus “war on terrorism,” even as they

remain silent about the U.S. global empire, are likewise contradictory. In chapter 1, “War and Peace,” the evils of war and warmongers and the benefits of peace are examined. In chapter 2, “The Military,” the evils of standing armies and militarism are discussed, including a critical look at the U.S. military. In chapter 3, “The War in Iraq,” the wickedness of the Iraq War is exposed. In chapter 4, “World War II,” the “good war” is shown to be not so good after all. In chapter 5, “Other Wars,” the evils of war and the warfare state are chronicled in specific wars: the Crimean War (1854–1856), the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), World War I (1914–1918), the Persian Gulf War (1990–1991), and the war in Afghanistan (2001–). In chapter 6, “The U.S. Global Empire,” the beginnings, growth, extent, nature, and consequences of the U.S. empire of bases and troops are revealed and critiqued. In chapter 7, “U.S. Foreign Policy,” the belligerence, recklessness, and follies of U.S. foreign policy are laid bare. Chapter One - War and Peace ______[p1]

Listen to "Christianity and WAR" on Spreaker.

WAR

The U.S. Global Empire

March 16, 2004

There is a new empire in town, and its global presence is increasing every day. The kingdom of Alexander the Great reached all the way to the borders of India. The Roman Empire controlled the Celtic regions of Northern Europe and all of the Hellenized states that bordered the Mediterranean. The Mongol Empire, which was the largest contiguous empire in history, stretched from Southeast Asia to Europe. The Byzantine Empire spanned the years 395 to 1453. In the sixteenth century, the Ottoman Empire stretched from the Persian Gulf in the east to Hungary in the northwest; and from Egypt in the south to the Caucasus in the north. At the height of its dominion, the British Empire included almost a quarter of the world’s population. Nothing, however, compares to the U.S. global empire. What makes U.S. hegemony unique is that it consists, not of control over great land masses or population centers, but of a global presence unlike that of any other country in history. The extent of the U.S. global empire is almost incalculable. The latest “Base Structure Report” of the Department of Defense states that the Department’s physical assets consist of “more than 600,000 individual buildings and structures, at more than 6,000 locations, on more than 30 million acres.” The exact number of locations is then given as 6,702 — divided into large installations (115), medium installations (115), and small installations/locations (6,472). This classification can be deceiving, however, because installations are only classified as small if they have a Plant Replacement Value (PRV) of less than $800 million. Although most of these locations are in the continental United States, 96 of them are in U.S. territories around the globe, and 702 of them are in foreign countries. But as Chalmers Johnson has documented, the figure of 702 foreign military installations is too low, for it does not include installations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Israel, Kosovo, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Qatar, and Uzbekistan. Johnson estimates that an honest count would be closer to 1,000. The number of countries that the United States has a presence in is staggering. According the U.S. Department of State’s list of “Independent States in the World,” there are 192 countries in the world, all of which, except Bhutan, Cuba, Iran, and North Korea, have diplomatic relations with the United States. All of these countries except one (Vatican City) are members of the United Nations. According to the Department of Defense publication, “Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country,” the United States has troops in 135 countries. Here is the list: Afghanistan Albania Algeria Antigua Argentina Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belgium Belize Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Brazil Bulgaria Burma Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Canada Chad Chile China Colombia Congo Costa Rica Cote D’lvoire Cuba Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Djibouti Dominican Republic East Timor Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Fiji Finland France Georgia Germany Ghana Greece Guatemala Guinea Haiti Honduras Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iraq Ireland Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Laos Latvia Lebanon Liberia Lithuania Luxembourg Macedonia Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Mali Malta Mexico Mongolia Morocco Mozambique Nepal Netherlands New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria North Korea Norway Oman Pakistan Paraguay Peru Philippines Poland Portugal Qatar Romania Russia Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia and Montenegro Sierra Leone Singapore Slovenia Spain South Africa South Korea Sri Lanka Suriname Sweden Switzerland Syria Tanzania Thailand Togo Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom Uruguay Venezuela Vietnam Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe This means that the United States has troops in 70 percent of the world’s countries. The average American could probably not locate half of these 135 countries on a map. To this list could be added regions like the Indian Ocean territory of Diego Garcia, Gibraltar, and the Atlantic Ocean island of St. Helena, all still controlled by Great Britain, but not considered sovereign countries. Greenland is also home to U.S. troops, but is technically part of Denmark. Troops in two other regions, Kosovo and Hong Kong, might also be included here, but the DOD’s “Personnel Strengths” document includes U.S. troops in Kosovo under Serbia and U.S. troops in Hong Kong under China. Possessions of the United States like Guam, Johnston Atoll, Puerto Rico, the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, and the Virgin Islands are likewise home to U.S. troops. Guam has over 3,200. Regular troop strength ranges from a low of 1 in Malawi to a high of 74,796 in Germany. At the time the most recent “Personnel Strengths” was released by the government (September 30, 2003), there were 183,002 troops deployed to Iraq, an unspecified number of which came from U.S. forces in Germany and Italy. The total number of troops deployed abroad as of that date was 252,764, not including U.S. troops in Iraq from the United States. Total military personnel on September 30, 2003, was 1,434,377. This means that 17.6 percent of U.S. military forces were deployed on foreign soil, and certainly over 25 percent if U.S. troops in Iraq from the United States were included. But regardless of how many troops we have in each country, having troops in 135 countries is 135 countries too many. The U. S. global empire — an empire that Alexander the Great, Caesar Augustus, Genghis Khan, Suleiman the Magnificent, Justinian, and King George V would be proud of.

The Bases of Empire March 17, 2004

A global empire like the United States needs overseas bases to accommodate its troops, now in 135 countries. Although the latest “Base Structure Report” of the Department of Defense admits to having 96 military installations in U.S. overseas territories and 702 military installations in foreign countries, it has been documented that this number is far too low. The official list of countries that we have bases in is as follows: Antigua Australia Austria Bahamas Bahrain Belgium Canada Columbia Cuba Denmark Egypt France Germany Greece Honduras Iceland Indonesia Italy Kenya Japan Luxembourg Netherlands New Zealand Norway Oman Peru Portugal Singapore Spain South Korea Turkey United Arab Emirates United Kingdom Venezuela To this must be added the bases that we have in Diego Garcia, Greenland, Hong Kong, Kwajalein Atoll, and St. Helena. This makes a total of 39 foreign locations that the United States officially has bases in, not counting bases in U.S. overseas territories like Guam, Johnston Atoll, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. But there are problems with this official list. First of all, it has some notable omissions. The Air Force Technical Applications Center in Thailand is not listed. And neither is Eskan Village and Prince Sultan Air Base in Saudi Arabia. The United States has had a troop presence in the former Soviet Republics of Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan since October of 2001, yet they are not listed either. The huge Camp Bondsteel in Kosovo is not even listed, although President Bush has spoken there. According to the Department of Defense publication, “Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country,” the United States has 2,997 active duty military personnel in Qatar. Yet, no base in listed in the Base Structure Report. Incredibly, no bases are even listed in Afghanistan, Kuwait, or Iraq. With critical omissions like these, God only knows how many more foreign bases we have that are not listed. The issue is not just how many countries the United States has bases in. The issue is U.S. troops on foreign soil. Having an official base just makes our foreign presence worse. It would be better for U.S. troops to patrol our border with Mexico than to patrol the borders of countries half way around the world that most Americans could not locate on a map.

Guarding the Empire

October 4, 2004 When faced with evidence that the U.S. Global Empire has troops and/or bases in the majority of countries on the planet, apologists for the warfare state and the “military-industrial complex” attempt to dismiss this U.S. global hegemony by claiming that it is the Marine guards at U.S. embassies overseas that account for our presence in so many countries. It is traditionally believed that the United States has an embassy in every foreign country and that every foreign country has an embassy in the United States. Most people also think that every U.S. embassy has an attachment of Marine guards to provide security for embassy personnel. Both of these assumptions are wrong. U.S. Embassies in Foreign Countries Of the 191 “Independent States in the World” besides the United States, there are 29 countries in which we do not have an embassy: Andorra Antigua and Barbuda Bhutan Comoros Cuba Dominica Grenada Guinea-Bissau Iran Kiribati Libya Liechtenstein North Korea Maldives Monaco Nauru Palau Republic of the Congo Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Seychelles Solomon Islands Somalia Tonga Tuvalu Vanuatu The United States does not have an embassy in the countries of Bhutan, Cuba, Iran, and North Korea because we do not have diplomatic relations with them. Many small countries in which the United States has no embassy are “covered” by another country. The U.S. ambassador to Spain is accredited to Andorra. The U.S. ambassador to Barbados is accredited to Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. The U.S. ambassador to Mauritius is accredited to Seychelles and Comoros. The U.S. ambassador to Senegal is accredited to Guinea-Bissau. The U.S. ambassador to the Marshall Islands is accredited to Kiribati. The U.S. ambassador to Switzerland is accredited to Liechtenstein. The U.S. ambassador to Sri Lanka is accredited to Maldives. The U.S. consul general in Marseille, France, is accredited to Monaco. The U.S. consul general in Florence, Italy, is accredited to San Marino. The U.S. ambassador to Papua New Guinea is accredited to the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. The U.S. ambassador to Kenya is accredited to Somalia. The U.S. ambassador to Gabon is accredited to Sao Tome and Principe. The U.S. ambassador to Fiji is accredited to Tonga, Tuvalu, and Nauru. The U.S. ambassador to the Philippines is accredited to Palau. The status of U.S. embassies sometimes changes. In some countries, like Antigua and Barbuda, Guinea-Bissau, Iran, and the Solomon Islands, we used to have an embassy, but it is now closed. The United States has an ambassador to the Republic of the Congo, but the embassy is temporarily collocated with the U.S. embassy in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly called Zaire). The Afghan embassy closed in January 1989 but then reopened in December 2001. In the Central African Republic, the embassy is currently operating with a minimal staff. The United States closed its embassy in Libya in May 1980 and then resumed embassy activities in February 2004 through a U.S. “interest section” in the Belgian embassy. Since June 2004, the United States has maintained a “liaison office” in Libya, but has no immediate plans for an embassy. New embassies had to be built in Kenya and Tanzania after they were bombed in August 1998. Foreign Embassies in the United States Just because the United States does not have an embassy in a particular country does not necessarily mean that that country does not have an embassy in the United States. Of the 191 “Independent States in the World” besides the United States, there are 18 countries that do not maintain an embassy in the United States: Andorra Bhutan Comoros Cuba Iran Kiribati North Korea Libya Maldives Monaco Nauru San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Solomon Islands Somalia Tonga Tuvalu Vanuatu As mentioned above, the United States does not have diplomatic relations with Bhutan, Cuba, Iran, and North Korea. All of these countries that do not maintain an embassy in Washington DC are members of the United Nations and have a representative of some kind at the UN in New York. There are therefore 11 of these countries that have an embassy in the United States even though we do not have one in their country: Antigua and Barbuda Dominica Grenada Guinea-Bissau Liechtenstein Palau Republic of the Congo Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Seychelles There are no countries in which the United States has an embassy that do not likewise have one on U.S. soil. Marine Security Guards The question of Marine guards providing security at our embassies is not an easy one to answer. All of our embassies have security measures of some kind, but all are not guarded by U.S. Marines. For security reasons (isn’t that always the excuse?), the government does not like to reveal which embassies have Marine guards and which embassies do not. Marine security guards are members of the Marine Security Guard Battalion headquartered at the Marine Corps base in Quantico, Virginia. Quantico is also the location of the Marine Security Guard School, where guards are trained to react to terrorism, fires, riots, demonstrations, and evacuations. The stationing of Marine Security Guards at U.S. embassies can be traced to The Foreign Service Act of 1946, which authorizes the Secretary of the Navy, “upon the request of the Secretary of State, to assign enlisted members of the Navy and the Marine Corps to serve as custodians under supervision of the Principal Officer at an Embassy, Legation or Consulate.” The first Marine security guards went to Tangier and Bangkok on January 28, 1949. By the end of May 1949, 303 Marines had been assigned to foreign posts. By 1953, this number had increased to 6 officers and 676 enlisted men. By 1956, the number of enlisted men was up to 850. There are currently over 1,200 Marines serving at over 130 posts abroad, in over 100 countries. Exact figures are not available, but in a report “Concerning the Role of Marine Security Guards in Securing U.S. Embassies and Government Personnel” given before the House Armed Services Committee Special Oversight Panel on Terrorism on October 10, 2002, by W. Ray Williams, the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Countermeasures and Information Security, the number of Marine security guards was given as 1,029 “at 131 US Missions abroad, soon to be 132 with the reactivation of a Marine Security Guard Detachment in Belgrade scheduled for January 2003.” He further stated that 19 additional detachments of Marine guards were to be added in the next five years, with a long-term goal of 1,352 Marine guards at 159 detachments. According to the U.S. State Department, as of August 2003, the United States had “over 1,200 Marines for the internal security of 132 U.S. embassies, missions, and consulates worldwide.” Marine security guards are organized into 7 regional companies. Company A headquarters is located in Frankfurt, Germany, and is responsible for 20 detachments in Eastern Europe. Company B headquarters is located in Nicosia, Cyprus, and is responsible for 18 detachments in northern Africa and the Middle East. Company C headquarters is located in Bangkok, Thailand, and is responsible for 18 detachments located in the Far East, Asia, and Australia. Company D headquarters is located in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, and is responsible for 26 detachments in Central and South America and the Caribbean. Company E headquarters is also located (with Company A) in Frankfurt, Germany, and is responsible for 16 detachments in Western Europe and Ottawa, Canada. Company F headquarters is located in Nairobi, Kenya, and is responsible for 11 detachments in Sub-Saharan Africa. Company G headquarters is located in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire, and is responsible for 12 detachments in West and Central Africa. Marine security guard companies are commanded by a lieutenant colonel. At each diplomatic post, there is a minimum of one detachment commander and five Marine security guards. This allows them to maintain one security post 24/7. Locations with more than one security post have more than five guards. About 40 percent of detachments have the 1/5 ratio of commander to guards, another 40 percent are between 1/6 and 1/10, and the remaining 20 percent have something greater than 1/10. After graduating from security guard school, a Marine can usually expect two fifteen-month duty tours. The U.S. Global Empire What, then, do embassies and Marine guards have to do with the U.S. Global Empire of troops and bases that garrison the planet? As mentioned at the onset of this article, apologists for the U.S. Global Empire attempt to dismiss our troop presence in so many countries by claiming that including Marines guarding embassies inflates the total number of countries in which we have a troop presence. The truth, however, is that whether Marine guards are counted or not, the United States still has a global empire that now encompasses 136 countries. The source for information on U.S. troops stationed abroad is the quarterly publication entitled “Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country.” This is published by a Department of Defense organization called the Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (DIOR). The latest edition that will be referenced in this article is dated March 31, 2004. Previous editions can be seen here. According to the DIOR, the information contained in its report of personnel strengths is provided directly by each branch of the U.S. Armed Forces; that is, the DIOR merely reports the information it receives. The DIOR publication does not indicate why troops are in a particular country, it merely reports the fact that they are there. The issue here is whether the Marine Corps troops listed as deployed on foreign soil includes Marine guards at embassies. If the figure given for Marines in each country does not include embassy guards, then the United States does in fact have troops in 136 countries. Case closed. There is no need for this article other than to point out that the United States has added one more country (Guyana) since the first time I addressed the subject of the U.S. Global Empire. But if the figure given for Marines in each country does include embassy guards, then what apologists for the U.S. Global Empire are saying is that the United States does not have troops in 136 countries because Marine guards should not be included. Therefore, so they say, the number of countries in which the U.S. has troops should be limited to those countries in which we actually have bases. Of course, that is a problem as well, but it is not under consideration here since I have previously addressed the subject of the bases of the U.S. Empire. Although the case could be made that these guards are what Lew Rockwell calls “armed servants for the spies and bureaucrats,” I am willing to agree with apologists for the U.S. Global Empire that Marine guards should not be counted when determining whether the United States has troops in other countries. This is also assuming that the “Personnel Strengths” document is accurate. The issue cannot be settled by merely asking the Marine Corps how it determines the number of Marines it has in each country. No one I spoke with in the DOD or the Marine Corps ever heard of the “Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country” document. And no one in the DOD or the Marine Corps that I sent the document to ever responded. Furthermore, when you start asking questions about Marines guarding U.S. embassies, DOD and Marine Corps officials get nervous (and sometimes downright belligerent) and start asking you questions about why you want the information. After studying the “Personnel Strengths” document, and after determining which countries have a U.S. embassy, it looks as though the figures given for Marines deployed to foreign countries do not include Marine guards at embassies. Of the 55 countries in which the United States does not have any troops (not just Marines), the following have a U.S. embassy: Angola Armenia Belarus Benin Brunei Burkina Faso Cape Verde Central African Republic Croatia Equatorial Guinea Gabon Gambia Holy See (The Vatican) Lesotho Marshall Islands Mauritania Mauritius Micronesia Moldova Namibia Panama Papua New Guinea Rwanda Samoa Slovak Republic Sudan Swaziland Tajikistan Uzbekistan If the figures include Marine guards, then this would mean that no U.S. embassy in any of these 29 countries had Marine security guards. Some countries in which the United States has Army, Navy, and/or Air Force troops have a U.S. embassy but no Marines are listed as being in the country: Belize Cambodia Eritrea Guyana Lebanon Madagascar Malawi Mongolia New Zealand Suriname Ukraine If the figures include Marine guards, then this would mean that no U.S. embassy in any of these 11 countries had Marine security guards. Other countries in which the United States has troops including Marines have a U.S. embassy but do not have the minimum number of 6 Marines necessary for embassy security guard duty. Albania Botswana Bulgaria Cameroon Democratic Republic of the Congo Guinea Iceland Laos Luxembourg Malaysia Mexico Morocco Romania Serbia and Montenegro Sri Lanka Sweden Tanzania Zambia Zimbabwe If the figures include Marine guards, then this would mean that no U.S. embassy in any of these 19 countries had Marine security guards. There are 13 countries in which the only troops listed are Marines: Azerbaijan Burundi Fiji Kyrgyzstan Latvia Mali Malta Mozambique North Korea Sierra Leone Togo Trinidad and Tobago Turkmenistan The countries of Azerbaijan, Burundi, Fiji, Sierra Leone, and Trinidad and Tobago do not have the minimum number of 6 Marines necessary for embassy security guard duty. If the figures include Marine guards, then this would mean that no U.S. embassy in these 5 countries had Marine security guards. We do not have an embassy in North Korea for Marines to guard. Likewise, there are 167 Marines in Cuba but the United States has no embassy there either. But supposing that the figure given for Marines in each country does include Marine security guards at embassies, we still have a problem. Most of the countries with a U.S. embassy that have the minimum number of 6 Marines that are necessary to provide embassy security guard duty also have Army, Navy, and/or Air Force troops as well. So whether the figures include Marine guards is irrelevant. The following countries have a U.S. embassy, troops from the Army, Navy, and/or Air Force, and at least 6 Marines: Afghanistan Algeria Argentina Australia Austria Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belgium Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina Brazil Burma Canada Chad Chile China Colombia Costa Rica Cote d’lvoire Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Djibouti Dominican Republic Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Estonia Ethiopia Finland France Georgia Germany Greece Guatemala Guinea Haiti Honduras Hungary Iceland India Indonesia/East Timor Iraq Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kuwait Liberia Lithuania Macedonia Nepal Netherlands Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Norway Oman Pakistan Paraguay Peru Philippines Poland Portugal Qatar Russia Saudi Arabia Senegal Singapore Slovenia Spain South Africa South Korea Switzerland Syria Thailand Tunisia Turkey Uganda United Arab Emirates United Kingdom Uruguay Venezuela Vietnam Yemen The “Personnel Strengths” document includes the country of East Timor under Indonesia so it is impossible to determine exactly how the 10 Marines in that region are divided between the countries. Of the 13 countries in which the only troops listed are Marines, 6 were previously eliminated because either the United States did not have an embassy in the country or there was not the minimum number of 6 Marines necessary for embassy security guard duty. This leaves only the following seven countries as potential examples of countries with a U.S. embassy guarded by Marines that should not be included in the total of 136 countries in which the United States has troops: Kyrgyzstan Latvia Mali Malta Mozambique Togo Turkmenistan But a comparison of the current “Personnel Strengths” document with the previous quarterly editions shows that this is not the case. For example, Kyrgyzstan, which is now listed as having 8 Marines, had 14 Marines three months ago and 27 Marines six months ago. And Malta, which is now listed as having 4 Marines, had 7 Marines three months ago and 3 Marines six months ago. This could not possibly be just Marine embassy guards. The next quarterly report of “Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country” is sure to have similar changes. So the fact remains: Marine guards or no Marine guards, the United States has troops in 136 countries. But even that figure is too low, for the United States also has troops in Dependencies and Areas of Special Sovereignty. These are territories controlled by countries that may be located thousands of miles away from the mother country. For example, the United States has troops in Great Britain and areas controlled by Great Britain such as Gibraltar (on the southern coast of Spain), Diego Garcia (an atoll in the Indian Ocean), and St. Helena (an island in the South Atlantic Ocean). The United States has a 234,022-acre Air Force Base in Greenland, a region controlled by Denmark since 1721. Then there is Kosovo (an autonomous province of Serbia) and Hong Kong (a special administrative region of China). Aside from the 50 states of the United States, there are also U.S. troops in areas we control like Guam (an island in the Pacific Ocean), Johnston Atoll (an atoll in the Pacific Ocean), Puerto Rico (an island commonwealth in the Caribbean Sea), and the U.S. Virgin Islands (islands between the Caribbean Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean, east of Puerto Rico). According to the “Personnel Strengths” document, the United States also maintains 23 army personnel in the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. After World War II, these island groups in the Pacific Ocean came under the control of the United States. This “Trust Territory” now consists of three sovereign countries (Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau) and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, a commonwealth of the United States. If these additional areas that have U.S. troops are counted, then it could be said that the United States has troops in 150 countries or territories. It is now easier to list the countries in which the United States does not have troops instead of the other way around. So, although this list could change tomorrow, the following countries are not officially reported as having any U.S. troops: Andorra Angola Armenia Belarus Benin Bhutan Brunei Burkina Faso Cape Verde Central African Republic Comoros Croatia Dominica Equatorial Guinea Gabon Gambia Grenada Guinea-Bissau Holy See (The Vatican) Iran Kiribati Lesotho Libya Liechtenstein Maldives Mauritania Mauritius Moldova Monaco Namibia Nauru Panama Papua New Guinea Republic of the Congo Rwanda Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Samoa San Marino Sao Tome and Principe Seychelles Slovak Republic Solomon Islands Somalia Sudan Swaziland Tajikistan Tonga Tuvalu Uzbekistan Vanuatu U.S. Foreign Policy In his Farewell Address, George Washington warned against “permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world” and said that the United States should have “as little political connection as possible” with foreign nations. But he also warned us about “those overgrown military establishments which, under any form of government, are inauspicious to liberty, and which are to be regarded as particularly hostile to republican liberty.” If any country ever had an overgrown military establishment, it is the United States and its military juggernaut. Before the recent Iraq war, the United States outspent the “evil” rogue nations of Iraq, Syria, Iran, North Korea, Libya, and Cuba on defense spending by a ratio of twenty-two to one. The actual amount that the United States spent on “defense” during fiscal year 2004 has been estimated by Robert Higgs to be about $695 billion. The United States is also the biggest arms exporter, accounting for about half of all global arms exports. Most of this spending could be eliminated if the United States returned to the foreign policy ideas of the Founders. Current U.S. foreign policy can only be described as reckless, interventionist, militaristic, and belligerent. This can lead to severe consequences, as Chalmers Johnson has pointed out in his incredible book Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire, “The suicidal assassins of September 11, 2001, did not u2018attack America,’ as political leaders and news media in the United States have tried to maintain; they attacked American foreign policy.” The U.S. Empire is greatly overextended. Buried on page 362 of the 9/11 Commission Report is an admission that the entire planet is our manifest destiny: Now threats can emerge quickly. An organization like al Qaeda, headquartered in a country on the other side of the earth, in a region so poor that electricity or telephones were scarce, could nonetheless scheme to wield weapons of unprecedented destructive power in the largest cities of the United States. In this sense, 9/11 has taught us that terrorism against American interests “over there” should be regarded just as we regard terrorism against America “over here.” In this same sense, the American homeland is the planet. The 9/11 attacks were just the beginning of a worldwide revolt against the current U.S. foreign policy of a global empire. Only a Jeffersonian foreign policy of peace, commerce, friendship, and no entangling alliances can arrest the menacing U.S. Empire.

What's Wrong with the U.S. Global

Empire?

May 2, 2005

Some questions are not meant to be answered. They are really requests phrased as questions. Here are a couple that I have received, followed by what is really being requested if one reads the entire contents of what was written: Question: Why do you write for that Rockwell fellow? Request: You should not write for Lew Rockwell because he is a libertarian nut who hates the state and the military. Question: Why don’t you move to another country? Request: You should move to another country (like France) because you are anti-American for not supporting the president and the war in Iraq. Some questions, however, are genuine: “I was wondering if you could please give me a few reasons why you think it is a negative thing to have a US presence in that many countries around the world.” I recently received the above question, which is apparently a belated response to my articles last year on the U.S. global empire: “The U.S. Global Empire,” “The Bases of Empire,” and “Guarding the Empire.” There I documented that the U.S. has an empire of troops and bases the world over and explained that what makes U.S. hegemony unique is that it consists, not of control over great land masses or population centers, but of a global presence unlike that of any other country in history. The question raised is an important one, and since the question seemed genuine — the questioner did not preface or conclude his question with the charge that I was a pacifist, a liberal, a communist, or a traitor because I don’t support the war in Iraq and don’t think it is right for our military to have troops in almost every country on the planet — I am now answering it in the form of this article. So what’s wrong with the U.S. global empire? In answer to the above query, I came up with ten things. The responses are not in any particular order, and could certainly be expanded upon further. 1. What’s right about it? This is perhaps the most important response because it puts the question right back where it should be — on those who support the U.S. global empire. If someone is going to advocate some activity, he should be responsible to explain why it is necessary or why it is a positive thing. It should not be left up those who don’t advocate that particular activity to explain what the potential negative effects are. Are there any really positive things that result from the United States having its troops scattered around the globe? I mean things that could never be achieved by some other way. I can’t think of any. This does not mean that no one benefits from the U.S. global empire. The military industrial complex benefits. Nationals contracted by the U.S. military in their country to work on U.S. military installations benefit. Stockholders in companies that serve as defense contractors might benefit. But do the American people as a whole benefit? 2. It is unnatural. It is not natural for the United States (or any country) to have an empire of troops and bases that encircles the globe. Why should any U.S. troops ever leave American soil or American territorial waters? Suppose that the countries of Tunisia, Sweden, and Kenya announced that they were going to build military bases in the United States. Or suppose that the countries of Pakistan, Cameroon, and Bolivia announced that they were sending troops to the United States. These would be viewed as acts of aggression. Yet, why is it that the American people think nothing of the United States garrisoning the planet? 3. It is very expensive. The money factor cannot be ignored. Even without fighting a war, it costs a lot of money (the American taxpayers’ money) to pay, house, feed, and provide medical care for thousands of American soldiers. Then there are the expenses for weapons, ships, tanks, fuel, etc. Robert Higgs has recently estimated that “the government’s total military-related outlays in fiscal year 2006 will be in the neighborhood of $840 billion — or, approximately a third of the total budget.” In Old Right conservative John T. Flynn’s “A Rejected Manuscript,” from Forgotten Lessons, a collection of his essays, he explains that “the oldest of all rackets for spending the people’s money is the institution of militarism. It creates a host of jobs — at low wages — in the armed services plus the far better paid and numerous jobs and dividends in the industries which produce the arms, provide the sailors and soldiers with food, clothes, medical care, and, juiciest of all, the weapons of war.” 4. It is against the principles of the Founding Fathers. Sending troops overseas, building military bases in foreign countries, and making alliances is foreign interventionism, pure and simple. The Founding Fathers recommended a noninterventionist foreign policy, and for good reason. George Washington warned against “permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” He also said: “The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is, in extending our commercial relations to have with them as little political connection as possible.” Thomas Jefferson stated: “I am for free commerce with all nations, political connection with none, and little or no diplomatic establishment. And I am not for linking ourselves by new treaties with the quarrels of Europe, entering that field of slaughter to preserve their balance, or joining in the confederacy of Kings to war against the principles of liberty.” John Quincy Adams would certainly not have approved of current U.S. foreign policy since he said that “America . . . goes not abroad seeking monsters to destroy.” Were they transported to the twenty-first century, would Washington, Jefferson, and Adams even recognize the American republic today as the same country in which they served as president? 5. It fosters undesirable activity. As I pointed out in my article “Should a Christian Join the Military?” Chalmers Johnson, of the Japan Policy Research Institute, in his seminal work Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire, has described the network of bars, strip clubs, whorehouses, and VD clinics that surround U.S. bases overseas. The former U.S. naval base at Subic Bay in the Philippines “had no industry nearby except for the u2018entertainment’ business, which supported approximately 55,000 prostitutes and a total of 2,182 registered establishments offering u2018rest and recreation’ to American servicemen.” At the annual Cobra Gold joint military exercise in Thailand: “Some three thousand prostitutes wait for sailors and marines at the South Pattaya waterfront, close to Utapao air base.” Johnson has also chronicled the excessive crime rates among American servicemen stationed in Okinawa — “the 58-year-long record of sexual assaults, bar brawls, muggings, drug violations, drunken driving accidents, and arson cases all committed by privileged young men who proclaim they are in Okinawa to protect the people from the dangers of political u2018instability’ elsewhere in East Asia.” 6. It increases hatred of Americans. One need look no further than the “welcome” our troops have received in Iraq. Of the 1,569 American military deaths in Iraq, 1,102 of them have occurred since the capture of Saddam Hussein. (The actual figures may in fact be higher — which means that more senseless deaths of Americans have occurred since the writing of this article). Why was Osama bin Laden so upset with the United States? He was outraged by the U.S. military presence in Saudi Arabia. In 2002, after two U.S. soldiers were acquitted by a U.S. military court in South Korea of negligent homicide in the deaths of two Korean schoolgirls, Koreans demonstrated, burned American flags, chanted anti-American slogans, and demanded that U.S. troops leave the country. Hatred of the United States is not a result of our freedoms and our values, it is a direct result of our intervention into the affairs of other countries and our military presence around the world. 7. It perverts the purpose of the military. The purpose of the U.S. military should be to defend the United States. That’s it. Nothing more. Using the military for any other purpose perverts the purpose of the military. The U.S. military has no business attempting to bring democracy to the world, remove dictators, spread goodwill, fight communism or Islam, guarantee the neutrality of any country, change a regime that is not friendly to the United States, train the armies of other countries, open foreign markets, protect U.S. commercial interests, provide disaster relief, or provide humanitarian aid. The U.S. military should be engaged exclusively in defending the United States, not defending other countries, and certainly not attacking them. What are U.S. troops doing overseas when the border between Mexico and the United States is not even secure? 8. It increases the size and scope of the government. There is no way a country can have hundreds of bases and thousands of troops overseas without a substantial and onerous bureaucracy at home. Cold warrior William F. Buckley admitted as much in his 1952 article in The Commonweal, “A Young Republican View”: “We have to accept Big Government for the duration — for neither an offensive nor a defensive war can be waged given our present government skills except through the instrumentality of a totalitarian bureaucracy within our shores.” Buckley went on to recommend that we support “large armies and air forces, atomic energy, central intelligence, war production boards and the attendant centralization of power in Washington.” It is no wonder that the “conservative” Buckley was branded by Murray Rothbard as “a totalitarian socialist,” and rightly so, for intervention abroad cannot but follow intervention at home. The practice of “national greatness” conservativism abroad and “leave us alone” conservatism at home, as espoused by Michael Barone, Andrew Sullivan, and assorted neoconservatives, is an impossibility. As Justin Raimondo explains: “It doesn’t work that way. We can’t have an Empire abroad, and a Republic at home (except in name only) for the simple reason that the tax monies it takes to build mighty fleets and bases all around the world, to police the earth and humble the wicked, must be enormous. Furthermore, the sheer power it takes to direct these armies, to say whether there shall be war or peace on a global scale, is necessarily imperial, and cannot be republican in any meaningful sense of the word. For this sort of power, i.e. military power, must be highly centralized in order to be effectively wielded: an interventionist foreign policy necessarily turns the President into an Emperor, as Congress has learned partly to its relief and often to its sorrow.” 9. It makes countries dependent on the presence of the U.S. military. This is especially true in countries where U.S. troops have had a presence for decades. Consider the case of Germany. The United States recently sought to punish Germany for leading international opposition to the war in Iraq by withdrawing some U.S. troops from German soil. The planned withdrawal of troops was designed to harm the German economy and make an example of Germany. But even if troop withdrawals are not retaliatory in nature, the fact remains that the local economies in the occupied countries suffer because they become dependent upon the presence of the U.S. military. The threat or even the mention of troop withdrawals causes unnecessary contention between nations. 10. The United States is not the world’s policeman. It’s a dirty job. It’s a thankless job. It’s an impossible job. And no, someone does not really have to do it. Why, then, do we even try? We cannot police the world. We have no right to police the world. It is the height of arrogance to try and remake the world in our image. Most of what happens in the world is none of our concern and certainly none of our business. If the people in a country don’t like their ruler, then they should get rid of him, not look to the United States to intervene. Actually, though, most of the time it is the United States that institutes a regime change. If Sunni and Shi’ite Muslims want to terrorize each other — it is a tragic thing, but nothing the United States should get involved in. If India and Pakistan want to endlessly debate the Kashmir Question, then let them endlessly debate it. Why should we get involved? What would we think if India or Pakistan tried to intervene in a border dispute between the United States and Mexico? If the Hutus and the Tutsis battle it out in Africa — it is a terrible thing but none of our business. If an individual American feels that strongly about either side, he can pray for peace, he can send money to the side he favors, or he can go to Africa and enlist in the Hutu or Tutsi army and fight. If North and South Vietnam have a quarrel — it is not worth the lives of over 58,000 Americans (the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC now lists 58,245 names), the wounding of 304,000 Americans, and the disabling of 75,000 of those wounded (over 23,000 were totally disabled) to intervene. It is not worth the life of one American. It is strange how advocates of U.S. wars, interventions, and militarism consider opponents of these things to be un-patriotic and anti-American when those who are for non-intervention are the ones concerned about the life of even one American being used as cannon fodder for the state. Being the world’s policeman also entails bribing countries with foreign aid — a subject I have explored elsewhere. Does this U.S. global presence mean that the United States has an empire? It is an empire in everything but name. Supposedly sovereign, free, and independent countries can’t even have an election without the United States intervening. Yes, there is a high probability of fraud in some foreign elections. But not only are foreign elections none of our business, how would we feel if China, Kenya, Belarus, or Botswana sent “observers” to supervise our elections because of the high probability of fraud? “Today,” as neoconservative Charles Krauthammer maintains, “the United States remains the preeminent economic, military, diplomatic, and cultural power on a scale not seen since the fall of the Roman Empire.” Yes, and if we are not careful we will go the way of the Roman Empire. The U.S. government’s foolish interventions have caused much of the world to view America as the new evil empire. Krauthammer also claims that “the international environment is far more likely to enjoy peace under a single hegemon. Moreover, we are not just any hegemon. We run a uniquely benign imperium.” Until, of course, a country disagrees with us — then it is bombs away.

Today Iraq, Tomorrow the

World

December 5, 2005

“We don’t seek empires. We’re not imperialistic.” ~ Donald Rumsfeld (2003) “If we want Iraq to avoid becoming a Somalia on steroids, we’d better get used to U.S. troops being deployed there for years, possibly decades, to come. If that raises hackles about American imperialism, so be it. We’re going to be called an empire whatever we do. We might as well be a successful empire.” ~ Max Boot (2003) “We’re an empire now.” ~ a senior adviser to President Bush (2004) The number in Germany is 69,395. The number in Japan is 35,307. The number in Korea is 32,744. The number in Italy is 12,258. The number in the United Kingdom is 11,093. I am not speaking of the number of car accidents last year in Germany, Japan, Korea, Italy, or the United Kingdom. And neither am I speaking of the number of poisonings, suicides, or armed robberies in any of these countries. No, I am speaking of something far more lethal: the continued presence of U.S. troops. According to the latest edition of the “Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country,” published by the Defense Department’s Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (DIOR), the U.S. has troops in 142 countries. This is up from the figure of 136 countries that the government was reporting the last time I addressed the subject of the number of countries under the shadow of the U.S. Global Empire. Additions to the list are Armenia, Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Iran, Malawi, Moldova, Slovak Republic, and Sudan. Subtractions are Eritrea and North Korea. Only 49 countries to go and the United States will have hegemony over the whole world. But it is worse than it appears. Counting the U.S. troops in territories, the officially reported number of countries or territories that the United States has troops in is now 155. It is not without cause that the twentieth century’s greatest proponent of liberty, and the greatest opponent of the state, Murray Rothbard (1926—1995), said that “empirically, taking the twentieth century as a whole, the single most warlike, most interventionist, most imperialist government has been the United States.” This foreign troop presence is, of course, directly opposite the foreign policy of the Founding Fathers:

In his Farewell Address, George Washington also warned against “permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” Could he have ever imagined the commitment of the United States to be the world’s policeman? Since the Spanish-American War of 1898, the foreign policy of the United States has been one of interventionism, which is always followed by its stepchildren belligerency, bellicosity, and jingoism. When televangelist Pat Robertson recently said that the United States government should “take out” the president of Venezuela, Hugo Chavez, he had a history of CIA assassinations and assassination schemes to go by. This certainly doesn’t excuse his remarks, but it is important to note that U.S. intervention abroad has not always been masked under the noble purposes of humanitarian relief or making the world safe for democracy. Because we live in an imperfect world of nation-states that is not likely to change anytime in the near future, the question of U.S. foreign policy cannot be ignored. Many libertarians make the mistake of expending all of their energies in an attempt to downsize the state by freeing the market and society from government interference while forgetting that “war,” in the immortal words of Randolph Bourne (1886—1918), “is the health of the state.” Libertarians who disparage the welfare state while turning a blind eye to the warfare state are terribly inconsistent. So, as Rothbard again said, since “libertarians desire to limit, to whittle down, the area of government power in all directions and as much as possible,” the goal in foreign affairs should be the same as that in domestic affairs: “To keep government from interfering in the affairs of other governments or other countries.” We should “shackle government from acting abroad just as we try to shackle government at home.” The state’s coercive arm of foreign intervention is the military. U.S. troops don’t “defend our freedoms.” As the Future of Freedom Foundation‘s Jacob Hornberger has so courageously pointed out, U.S. troops serve not as a defender of our freedoms but instead simply as a loyal and obedient personal army of the president, ready and prepared to serve him and obey his commands. It is an army that stands ready to obey the president’s orders to deploy to any country in the world for any reason he deems fit and attack, kill, and maim any “terrorist” who dares to resist the U.S. invasion of his own country. It is also an army that stands ready to obey the president’s orders to take into custody any American whom the commander in chief deems a “terrorist” and to punish him accordingly. To say that U.S. troops “defend our freedoms” is to say that my freedom to write this article right now that is critical of the U.S. government’s foreign policy is a direct result of the recent U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. That may sound ridiculous, but it is no more ridiculous than saying that U.S. troops “defend our freedoms” when what they actually do is bomb, invade, and occupy other countries. “Well,” I can hear the retort, “if it wasn’t for U.S. troops halting the German menace we would all be speaking German right now.” I suppose this is the same Germany that couldn’t cross the English Channel and invade Great Britain. And how does that justify keeping 69,395 U.S. troops on German soil over sixty years later? There is, therefore, one element of foreign policy that I would like to touch on: the role of the U.S. military in foreign affairs. It should be quite obvious from my writings on the U.S. empire (“The U.S. Global Empire,” “The Bases of Empire,” “Guarding the Empire,” and “What’s Wrong with the U.S. Global Empire“) that I don’t agree with Max Boot’s statement that “on the whole, U.S. imperialism has been the greatest force for good in the world during the past century.” That being said, the subject to be addressed is what should be done with the U.S. military in order to dissolve the U.S. empire and return to the nonintervention policy of the Founders. Today Iraq, tomorrow the world. The first thing that needs to be done is to get out of Iraq before the blood of one more American is shed on Iraqi soil. I have elsewhere shown that it is a simple matter to withdraw from Iraq in not only a safe, reasonable, and timely manner, but also in a just manner. That was back on August 8, when the number of wasted American lives was “only” 1,827. Three hundred more American soldiers have died since then. And for what? Three hundred more sets of American parents have suffered the loss of a child. And for what? Six hundred more sets of grandparents have suffered the loss of a grandchild. And for what? Many hundreds more brothers and sisters have lost a brother, or in some cases, a sister. And for what? Untold numbers of friends and acquaintances have lost the same. And for what? It is the warmongers who are anti-American, not us “anti-war weenies.” We never considered the shedding of the blood of even one American to be “worth” whatever it is that U.S. troops are now dying for. As I have elsewhere said: “Bringing democracy to Iraq and ridding the country of Saddam Hussein is not worth the life of one American. What kind of government they have and who is to be their u2018leader’ is the business of the Iraqi people, not the United States.” We should withdraw our forces, not because the war is going badly, not because too many American troops are dying, and not because the war is costing too much. We should withdraw our troops because the war was a monstrous wrong from the very beginning. Withdraw from Iraq today, and withdraw from the rest of the world tomorrow. After the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Iraq, the rest of the world should be put on notice: you’re next. Instead of listening to the BRAC Commission recommendations about which bases to close in the United States, Congress should close all foreign bases first. Instead of reading documents like Defense Planning Guidance or Rebuilding America’s Defenses, Congress should have read Murray Rothbard: The primary plank of a libertarian foreign policy program for America must be to call upon the United States to abandon its policy of global interventionism: to withdraw immediately and completely, militarily and politically, from Asia, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, from everywhere. The cry among American libertarians should be for the United States to withdraw now, in every way that involves the U.S. government. The United States should dismantle its bases, withdraw its troops, stop its incessant political meddling, and abolish the CIA. It should also end all foreign aid — which is simply a device to coerce the American taxpayer into subsidizing American exports and favored foreign States, all in the name of “helping the starving peoples of the world.” In short, the United States government should withdraw totally to within its own boundaries and maintain a policy of strict political “isolation” or neutrality everywhere. This is certainly a policy that could be implemented. How many countries in the world do the countries of Italy, Argentina, and Iceland have troops and bases in? How about Switzerland, Mongolia, and Lithuania? Are any of these countries in danger of being attacked because they don’t have an empire of troops of bases? There is absolutely no reason why the United States has to have an empire of troops and bases that encircles the world that it presently has. This policy is one of political isolation. It doesn’t mean that the United States should refuse to participate in the Olympics, refuse to issue visas, refuse to trade, refuse to extradite criminals, refuse to allow travel abroad, or refuse to allow immigration. It is a policy, not of isolationism, but of non-interventionism. It is also the policy of the Founding Fathers, like Thomas Jefferson:

No judgment, no meddling, no political connection, and no partiality. What is wrong with the wisdom of

Jefferson? Today Iraq, tomorrow the world — and then what? Once American troops are withdrawn from garrisoning the planet, they should be prevented from doing

so again. One way to do this would be to adopt the Amendment for Peace, proposed by U.S. Marine Corps Major General

Smedley Butler (1881— 1940): 1. The removal of

members of the land armed forces from within the continental limits of the United States and the Panama Canal Zone

for any cause whatsoever is hereby prohibited. 2. The vessels of the United States Navy, or of the other branches

of the armed service, are hereby prohibited from steaming, for any reason whatsoever except on an errand of mercy,

more than five hundred miles from our coast. 3. Aircraft of the Army, Navy and Marine Corps is hereby prohibited

from flying, for any reason whatsoever, more than seven hundred and fifty miles beyond the coast of the United

States. This amendment is a great starting point. Obviously, the Panama Canal Zone statement is now irrelevant. And

whether the government could be trusted to not use “an errand of mercy” as a covert operation is now very

debatable. Major Butler believed that his amendment “would be absolute guarantee to the women of America that their

loved ones never would be sent overseas to be needlessly shot down in European or Asiatic or African wars that are

no concern of our people.” He also reasoned that because of “our geographical position, it is all but impossible

for any foreign power to muster, transport and land sufficient troops on our shores for a successful invasion.” In

this Butler was echoing Jefferson, who recognized that geography was one of the great advantages of the United

States: The insulated state in which nature has placed the American continent should so far avail it that no spark

of war kindled in the other quarters of the globe should be wafted across the wide oceans which separate us from

them. At such a distance from Europe and with such an ocean between us, we hope to meddle little in its quarrels or

combinations. Its peace and its commerce are what we shall court. But even without the advantage of geography, a

policy of non-intervention is sufficient, as Congressman Ron

Paul (R-TX) has pointed out: “Countries like

Switzerland and Sweden who promote neutrality and non-intervention have benefited for the most part by remaining

secure and free of war over the centuries.” What, then, would become of our military if a strict

non-interventionist policy of peace and neutrality were adopted? For starters, perhaps the Department of Defense

could then actually do something to “defend our freedoms” like guard our borders and patrol our coasts. The

military could be scaled back considerably (along with what Robert Higgs has estimated to be its $840 billion budget), with militias picking up the slack, as

William Lind has recently pointed out here and

here. Some say that Jefferson’s ideals are not practical

in a post-9/11 world. To them I offer the wisdom of Representative Paul, who has described a foreign policy for peace in these words: Our troops would be

brought home, systematically but soon. The mission for our Coast Guard would change if our foreign policy became

non-interventionist. They, too, would come home, protect our coast, and stop being the enforcers of bureaucratic

laws that either should not exist or should be a state function. All foreign aid would be discontinued. A foreign

policy of freedom and peace would prompt us to give ample notice before permanently withdrawing from international

organizations that have entangled us for over a half a century. US membership in world government was hardly what

the founders envisioned when writing the Constitution. The principle of Marque and Reprisal would be revived and

specific problems such as terrorist threats would be dealt with on a contract basis incorporating private resources

to more accurately target our enemies and reduce the chances of needless and endless war. The Logan Act would be

repealed, thus allowing maximum freedom of our citizens to volunteer to support their war of choice. This would

help diminish the enthusiasm for wars the proponents have used to justify our world policies and diminish the

perceived need for a military draft. If we followed a constitutional policy of non-intervention, we would never

have to entertain the aggressive notion of preemptive war based on speculation of what a country might do at some

future date. Political pressure by other countries to alter our foreign policy for their benefit would never be a

consideration. Commercial interests and our citizens investing overseas could not expect our armies to follow them

and protect their profits.

Update on the Empire

February 19, 2007 If it is true, as Ambrose Bierce (1842—1914) said, “War is God’s way of teaching Americans geography,” then empire must be God’s way of making Americans masters of the subject since the United States now has troops in 159 different regions of the world. We know this is true, not because some opponent of U.S. imperialism says so, but because the Department of Defense publishes a quarterly report called the “Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country.” Although these reports used to be issued by the Defense Department’s Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (DIOR), they are now prepared by the Statistical Information Analysis Division of the Defense Manpower Data Center. The latest report is dated September 30, 2006. Previous reports can be seen here. I first reported on this in an article published on March 16, 2004, and called “The U.S. Global Empire.” There I documented that the U.S. had troops in 135 countries, plus 14 territories that were not sovereign countries — some controlled by the United States and some controlled by other countries. I then showed on October 4, 2004, in “Guarding the Empire,” that the U.S. empire had increased to 150 different regions of the world. The last time I reported on the extent of the empire, December 5, 2005, in “Today Iraq, Tomorrow the World,” it had grown to encompass 155 different regions of the world. Today it pains me to report that the U.S. empire has now extended its tentacles to 159 regions of the world: 144 countries and 15 territories. To the original list of 135 countries I gave in “The U.S. Global Empire” can now be added: Angola Rwanda Armenia Slovakia Gabon Somalia Guyana Sudan Moldova Uzbekistan North Korea can be removed from the list. Yes, the “Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country” document that I originally used in 2004 said that there were four U.S. Marines stationed in the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea. Since there are 192 countries in the world besides the United States, this means that the U.S. military has troops in over 70 percent of the world’s countries. And this doesn’t include territories that are not sovereign countries. The 15 territories in which the United States now has troops are: American Samoa Micronesia Diego Garcia Northern Mariana Islands Gibraltar Palau Guam Puerto Rico Greenland St. Helena Hong Kong Virgin Islands Kosovo Wake Island Marshall Islands The Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Palau, and the Northern Mariana Islands make up the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and Wake Island are all territories of the United States. Here we might ask, not why does the United States have troops in these areas, but why does the United States have control of these territories to begin with? Although Donald Rumsfeld once claimed that the United States is not imperialistic and doesn’t seek empires, what else are you going to call this global presence in 159 regions of the world? Do all these countries want U.S. troops on their soil? Is there really any reason why the United States still has 64,319 troops in Germany, 33,453 troops in Japan, and 10,449 troops in Italy — sixty years after World War II? And what are we doing with 1,521 troops in Spain, 414 troops in Honduras, and 347 troops in Australia? And why do we have 31 soldiers in Cote D’Ivoire? Cote D’What? Cote D’Where? How many Americans can locate Cote D’Ivoire on a map or have ever heard of it? How many even care? (For the record, Cote D’Ivoire is next to Burkina Faso.) Scholarly advocates of American imperialism, like CFR Senior Fellow Max Boot, reject the term imperialism, but hold, like Boot, that the United States “should definitely embrace the practice.” Boot subscribes to what can be called twenty-first-century gunboat diplomacy. He believes that the United States should impose the rule of law, property rights, and free speech on Iraq “at gunpoint if need be.” Since “Iran and other neighboring states won’t hesitate to impose their despotic views on Iraq; we shouldn’t hesitate to impose our democratic views.” Less sophisticated apologists for U.S. interventionism and imperialism, along with the usual assortment of chickenhawks, armchair warriors, Bush lovers, Christian warmongers, Republican Party loyalists, and other “conservatives” who defend the military and the warfare state, attempt to dismiss U.S. global hegemony over the majority of the planet by claiming that many of the U.S. troops stationed abroad are just embassy guards. Since I have already showed in “Guarding the Empire” that it definitely is not the Marine guards at U.S. embassies overseas that account for the U.S. troop presence in so many countries, I will not address that point again here. The other argument is that the presence of U.S. troops in so many countries is really not an issue because in some countries the United States has only a handful of its soldiers. Now, it is true that the United States only has a handful of troops stationed in some countries (e.g., 9 in Albania, 7 in Latvia, 3 in Laos), but focusing on how few troops are actually in some countries misses the point entirely. The issue is U.S. troops on foreign soil. They have no business there. Period. No bases, no troops, and no military advisors. Echoing the inscription on the Liberty Bell, President Bush closed his second inaugural address with the statement that “America, in this young century, proclaims liberty throughout all the world, and to all the inhabitants thereof.” But rather than proclaiming liberty, the stationing of soldiers in 159 different regions of the world and garrisoning the planet with military bases does just the opposite. Instead of proclaiming liberty, it proclaims imperialism, interventionism, militarism, and jingoism — all with devastating consequences for those countries that dare to question American hegemony.

The Beginnings of Empire

February 26, 2007 “We don’t seek empires. We’re not imperialistic. We never have been. I can’t imagine why you’d even ask the

question.” ~ Donald Rumsfeld (April 2003) And we can’t

imagine why Rumsfeld is so ignorant of

American military history, especially since Vice President Dick Cheney calls him “the finest Secretary of Defense

this nation has ever had,” and especially since the Department of Defense, which he ran for six years, publishes a

quarterly report that reveals the extent of America’s global troop presence, now up to 159 different regions of the world. I have referred to this

report (“Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country”) in several previous articles.

The DOD now has these quarterly reports online for the years 1950 and 1953 through the

present. What they show is that the U.S. global empire is not a recent phenomenon. One would think that after World

War II, all U.S. forces would have been brought home — or at least brought home from every place except Western

Europe and Japan. Think again. The U.S. global empire was well in place soon after World War II. According to the

“Personnel Strengths” document for 1950 (the oldest available), the

United States had troops in about 100 different countries and territories. Here is the list: Alaska Afghanistan

Algeria Argentina Australia Austria Azores Belgium Bermuda Bolivia Brazil British West Indies Federation Bulgaria

Burma Canada (including Newfoundland) Canal Zone Caroline Islands (Truk, Palau) Ceylon Chile Colombia Costa Rica

Cuba Cyprus Czechoslovakia Denmark Dominican Republic Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Eritrea Ethiopia Finland France

Germany Greece (& Crete) Greenland Guatemala Haiti Hawaii Honduras Hong Kong Hungary Iceland India Indo-China

(Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia) Indonesia Iran Iraq Ireland (Eire) Israel Italy Japan Jerusalem Johnston Island Korea

Lebanon Liberia Libya (Tripoli) Luxembourg Mariana Islands Marshall Islands Mexico Midway Morocco Netherlands New

Zealand Nicaragua Norway Pakistan Panama (Republic of) Paraguay Peru Philippines Poland Portugal Puerto Rico

Rumania Ryukyus (Okinawa) Samoan Islands Saudi Arabia Singapore Spain Sweden Switzerland Syria Taiwan Thailand

Trieste Turkey Union of South Africa United Kingdom Uruguay USSR (Russia) Venezuela Virgin Islands Volcano Islands

(Iwo Jima) Yugoslavia We still have troops in some of the same places. And no, they are not all embassy guards, as

is explained here and here. And what has having troops in all of these places since

World War II resulted in? Nothing but wars and military interventions. Vietnam veteran and peace advocate

James Glaser has documented the sixty-five official

foreign military actions since World War II that have been approved by Congress to qualify the combatants for

membership in the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). A paper based

on extensive research of American military actions in foreign countries that was presented at the 2002 annual

meeting of the Southern Political Science Association in Savannah, Georgia, documented these and other

unofficial actions, concluding in part: Analysis of all United States military actions since the end of World

War II show that America has engaged in 263 military actions. A third of these occurred before 1991, while the

United States initiated 176 of these between 1991 and 2002. World War II was not the beginning of the U.S.

empire. Between the two world wars, U.S. troops were sent to Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Russia, Panama,

Honduras, Yugoslavia, Guatemala, Turkey, and China. But World War I was not the beginning either. Before we

tried to make the world safe for democracy, U.S. troops were sent to Nicaragua, Panama, Honduras, the Dominican

Republic, Korea, Cuba, Nicaragua, China, and Mexico. Although we might begin the U.S. empire with the seizure

from Spain of Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam during the Spanish-American War of 1898, we need to

go back a few years earlier to U.S. intervention in Hawaii. Many Americans know that Hawaii became the 50th

state in 1959; few Americans know what led up to the annexing of the island chain in 1898.

Ninety-Five Years to Go

April 7, 2008 “Make it a hundred” ~ John McCain Although U.S. troops have been in Iraq for five years now, we have only just begun. We can expect the great

grandchildren of the current U.S. soldiers in Iraq to be there as well — if John McCain has his way. This assumes,

of course, that these soldiers make it back to the United States breathing and in one piece so that they can have

children. Speaking at a January town hall meeting in New Hampshire, Senator McCain was asked about President Bush’s

comment about the United States staying in Iraq for fifty years. His reply to “Make it a hundred,” although it was harshly

criticized, did not keep him from winning primaries and becoming the Republican presidential nominee. After all,

said McCain, “We’ve been in Japan for 60 years. We’ve been in South Korea 50 years or so. That would be fine with

me.” The senator is not the only one to make a statement like that. Someone at National Review said

last year: “Ladies and gentlemen: Our Problems are here, there, and everywhere. They will last our lifetime. You

have heard of the Thirty Years’ War. This is ours — if not our Hundred Years’ War.” McCain did go on to condition

the U.S. occupation on “as long as Americans are not being injured or harmed or wounded or killed.” But when asked

about his statement on “Face the Nation,” the man who would be president remarked that “Americans aren’t concerned” about troops in

Iraq for the next 10,000 years. He also told a reporter “that

U.S. troops could be in Iraq for u2018a thousand years’ or u2018a million years,’ as far as he was concerned.” Now

he says that he “will

never set a date for withdrawal.” It should come as no surprise that the United States will have troops in Iraq for

many years to come. After all, there are still 57,080 U.S. soldiers stationed in Germany, 9,855 U.S. soldiers

stationed in Italy, 32,803 U.S. soldiers stationed in Japan, and 27,014 U.S. soldiers stationed in Korea. But even

where the United States did not fight a war, there are large numbers of U.S. troops to be found. There are 1,286

U.S. soldiers stationed in Spain and 9,825 soldiers stationed in the United Kingdom. It should also come as no

surprise that the United States has troops in Iraq in the first place. We would probably have U.S. forces there

regardless of whether we went to war. You see, there are U.S. soldiers stationed in about 70 percent of the world’s

countries. The Defense Department freely and publicly acknowledges this. In fact, the DOD issues a quarterly

report, the “Active Duty Military Personnel Strengths by Regional Area and by Country,” that provides this

information. The latest

report is dated September 30, 2007. Previous reports can be seen here. To recap on

the extent of U.S. troop presence around the globe, I first reported on this in an article published on March 16,

2004, titled “The U.S. Global Empire.” There I

documented that the U.S. had troops in 135 countries, plus 14 territories controlled by the United States or some

other country. I then showed on October 4, 2004, in “Guarding the Empire,” that the U.S. empire had increased to

150 different regions of the world. The third time I reported on the extent of the empire, December 5, 2005, in

“Today Iraq, Tomorrow the World,” that number had

grown to 155. The last time I updated the status of the U.S. global empire, in “Update on the Empire,” I revealed that U.S. soldiers were

stationed in 159 regions of the world: 144 countries and 15 territories. Not much has changed since then. The

United States has withdrawn its small contingent of military personnel from the British territories of Gibraltar

and St. Helena, but now has four sailors stationed in the British territory of Bermuda. New countries with U.S.

troops are Belarus, Croatia, and Tajikistan. There is one country that lost U.S. troops — Fiji. Although the Trust

Territory of the Pacific Islands doesn’t exit anymore, the DOD has been reporting the presence of American troops

there for years. This Trust Territory included what are now the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated

States of Micronesia, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and the Republic of Palau. The DOD now

reports U.S. troop presence in what was this Trust Territory differently. Since the DOD used to just report the

total number of U.S. troops stationed in the entire region, I was counting this as four territories with U.S.

troops. The Marshall Islands, Micronesia, and Palau are technically independent countries, but are associated with

the United States under a Compact of Free Association. The United States provides financial aid to these sovereign

regions, including many U.S. domestic programs, in exchange for allowing the United States to provide for their

defense; that is, allow the United States to build bases, station troops, and otherwise use the islands for

“defense-related” purposes. The DOD now just reports that there are seventeen Army personnel stationed in the

Marshall Islands. This would be for the U.S. Army’s Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site. So,

according to the Defense Department’s latest “Personnel Strengths” report, the United States now has troops

stationed in 147 countries and 10 territories. This is the greatest number of countries that the United States has

ever had troops in. These numbers are not the result of Marine embassy guards stationed at U.S. embassies, as I

showed in “Guarding the Empire.” To avoid giving a

complete list, I refer the reader to the original list of 135 countries I gave in “The U.S. Global Empire.” From this list should be subtracted

Fiji and North Korea, and to this list should be added Angola, Armenia, Belarus, Croatia, Gabon, Guyana, Marshall

Islands, Moldova, Rwanda, Slovakia, Somalia, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. True, U.S. troop presence in some

countries and territories is quite small. But what are we doing with 403 soldiers in Honduras, 140 soldiers in

Australia, and 126 soldiers in Greenland? John McCain insists that the issue in Iraq is “not American presence;

it’s American casualties.” Most Americans would probably agree since there is hardly a sound of protest over the

U.S. troops that are still in Germany, Italy, Japan, and Korea after fifty or sixty years. The U.S. global empire

of troops and bases has been around for so long that it is generally accepted by most Americans. I explained a few

years ago in “What’s Wrong with the U.S. Global

Empire?” exactly what is wrong a foreign policy of empire: it’s not right, it’s unnatural, it’s very expensive,

it’s against the principles of the Founding Fathers, it fosters undesirable activity, it increases hatred of

Americans, it perverts the purpose of the military, it increases the size and scope of the government, it makes

countries dependent on the presence of the U.S. military, and finally, because the United States is not the world’s

policeman. What would Americans think if Russia or China built bases in the United States and stationed thousands

of troops on our soil? They would be outraged, regardless of whether any U.S. citizens were harmed. In fact, most

Americans would be incensed if Russian, China, or any other country sent just a handful of troops to the United

States — even though the United States does the same thing to scores of other countries. Would it be okay if all of